EN A BRICK WANTS TO BE SOMETHING''

whilst(同时) giving an

architecture(建筑学) lecture. Today,

twenty years later, the ''

Louis

Kahn-The Power of Architecture'' exhibition

has just given me the chance to discover more about the

complex(复合体) and

nomadic(游牧的) life of the real man who talked to

this Brick.

''If you think of Brick, you say to

Brick, ‘What do you want, Brick?’ And Brick says

to you, ‘I like an

Arch(弓形).’ And if you say to Brick, ‘Look, arches

are expensive, and I can use a

concrete(混凝土的)

lintel(过梁)

over you. What do you think of that, Brick?’

Brick says, ‘I like an Arch.’ And it’s

important, you see, that you honor the material that you

use. [..] You can only do it if you honor the brick and

glorify(赞美)

the brick instead of

shortchanging(欺骗) it.''

Louis Kahn.

Transcribed(转录) from the 2003

documentary(记录的) 'My Architect: A Son’s

Journey by Nathaniel Kahn'. Master class at Penn,

1971.

Louis Kahn working on Fisher House

design, 1961.

Louis Kahn working on Fisher House

design, 1961.

© Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

The most important projects of the American

architect(建筑师) Louis

Kahn are

extensively(广阔地) documented in the

''

Louis Kahn-The Power of

Architecture(建筑学)'' exhibition which runs

until the

11th of August

2013 at

the

Vitra Design Museum in

Weil am Rhein,

Germany. In

unfolding

Kahn’s

architectural(建筑学的)oeuvre(全部作品)

through a

selection(选择) of

watercolours(水彩画),

pastels(粉蜡笔) and

charcoal(木炭) drawings created during his travels

in Italy, Greece and Egypt to name a few, one thing becomes

apparent(显然的). His skill, not only as an architect but also as

an artist and

illustrator(插图画家).

The exhibition

showcases(陈列橱) Kahn’sdiverse(不同的) range of architecture and

photographs of his beautiful spatial(空间的) compositions and buildings which

display powerful universal(普遍的) symbolism(象征).

Highlights(加亮区) include a four-meter-high model of

the

Philadelphia’s City Tower

(1952-57),

as well as the previously unreleased film shot by

Louis Kahn's son

Nathanial, who was

only 11 years old when his father died.

Louis Kahn in front of a model of the

City Tower Project in an exhibition at Cornell University, Ithaca,

New York, February 1958.

Louis Kahn in front of a model of the

City Tower Project in an exhibition at Cornell University, Ithaca,

New York, February 1958.

© Sue Ann Kahn.

Salk Institute in La Jolla, California,

Louis Kahn, 1959–65.

Salk Institute in La Jolla, California,

Louis Kahn, 1959–65.

© The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, photo:

John Nicolais.

Louis I. Kahn and Nathaniel

Kahn, ca.1970.

Louis I. Kahn and Nathaniel

Kahn, ca.1970.

Photo by Harriet Pattison, © 2003 Louis Kahn Project,

Inc.

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh(孟加拉国), Louis Kahn, 1962–83

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh(孟加拉国), Louis Kahn, 1962–83

Directed by

Nathanial

Kahn, and co-produced with

Susan Rose Behr,

the film ‘

My Architect: A Son’s Journey’

(2003), unveils

Nathaniel Kahn’s

attempt to learn more about his father’s

complex(复杂的) life using

the

haunting(不易忘怀的),

monumental(不朽的) creations(创造) as

the

medium(方法) with which to discover the man who

designed them. This is

a journey of love, art,

betrayal(背叛) and forgiveness(宽恕), especially when you realise how

rife(普遍的) this man’s life was with secrets and

chaos(混沌). His marriage to a woman (

Esther

Israeli), the daughter they had, his long-term

relationship with an

architect(建筑师) (

Anne Tyng), with

whom he had another daughter and then a long-term relationship with

the

landscape(风景) architect (

Harriet

Pattison), who is your mother;

add to this the

fact that the members of this

complicated(难懂的) trio(三重唱) didn't meet until Kahn's funeral,

and you

have all the elements(基础) of

a script for the perfect drama(戏剧) -

which is based on a true story!Thankfully however, with a

happy end, as

Nathanial

in the film, finds

the answers he's been searching for hidden

inside

Kahn's

magnum(大酒瓶) opus(作品) ''

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban,

the National Assembly Building'' in

Dhaka,

Bangladesh

(1962).

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh(孟加拉国), Louis Kahn, 1962–83

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh(孟加拉国), Louis Kahn, 1962–83

© Raymond Meier.

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh, Louis Kahn, 1962–83.

National Assembly Building in Dhaka,

Bangladesh, Louis Kahn, 1962–83.

© Raymond Meier.

Indian Institute of Management,

Ahmedabad.

Indian Institute of Management,

Ahmedabad.

Indian Institute of Management,

Ahmedabad.

Indian Institute of Management,

Ahmedabad.

© Alessandro Vassella, 1970.

Whilst Nathanial Kahn

brings a degree of light upon his own

'family's issues', the element(元素) ofLIGHT

itself was always his father’s

obsession(痴迷). It was the

protagonist(主角) of his designs, both inside and

outside his buildings and danced across the walls he built,

changing

continuously(连续不断地) throughout the course of the day.

Unlike other

architects(建筑师), his

palette(调色板) of materials

leaned(倾斜) heavily towards

textured(有织纹的)BRICK

and

bare(空的) concrete(具体物) with astonishing

facility(设施), creating spaces both highly

functional(功能的)and spiritually

uplifting(令人振奋的).

In 1904, at the age of three, Kahn suffered severe(严峻的) burns to his face and hands marking

him for life. Who would have ever thought then that his

preferred drawing material would have been

charcoal

with which

he

sketched(画素描或速写)

''objects'' that

went on to become some of the most important buildings of the 20th

century during the final two

decades(十年) of his life. Some of these

masterpieces(杰作) include; The

Salk Institute for

Biological Studies in La Jolla, California (1959); the

''

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban, the National Assembly

Building'' of

Bangladesh(孟加拉国) in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962); the

Phillips

Exeter Academy Library in New Hampshire (1965), the

Kimbell Art

Museum in

Fort Worth, Texas (1966), and the

massive(大量的) granite-block

memorial to American

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (designed 1973-74) on the tip of

Roosevelt Island in New York’s East River, which was

posthumously(死后的) completed in October 2012.

FDR Four Freedoms Park

(designed 1973-74) on the

tip of Roosevelt Island in New York’s East River. Completed

in October 2012.

FDR Four Freedoms Park

(designed 1973-74) on the

tip of Roosevelt Island in New York’s East River. Completed

in October 2012.

© 2013 Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms

Park.

'I had this thought that a memorial

should be a room and a garden. That's all I had. Why did I want a

room and a garden? I just chose it to be the point of departure.

The garden is somehow a personal nature, a personal kind of control

of nature. And the room was the beginning

of architecture(建筑学). I had this sense, you see, and the room

wasn't just architecture, but was an

extension(延长) of self.'

Louis Kahn,

transcript(成绩单) from a lecture at the Pratt

Institute in 1973.

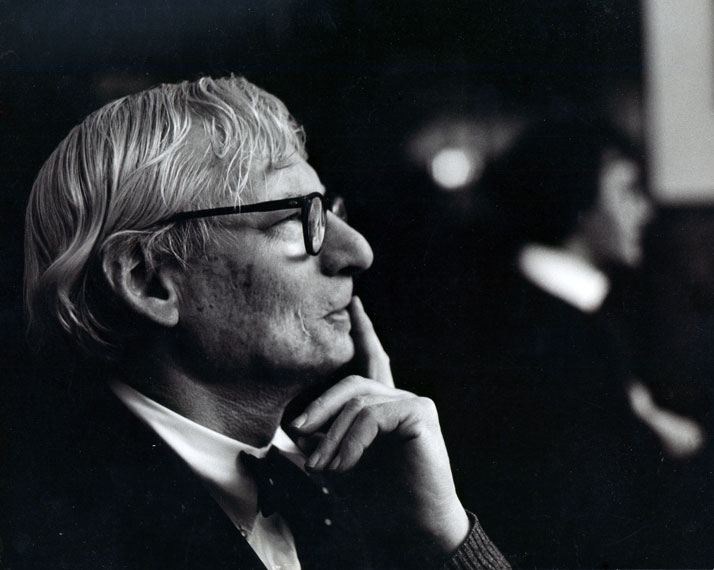

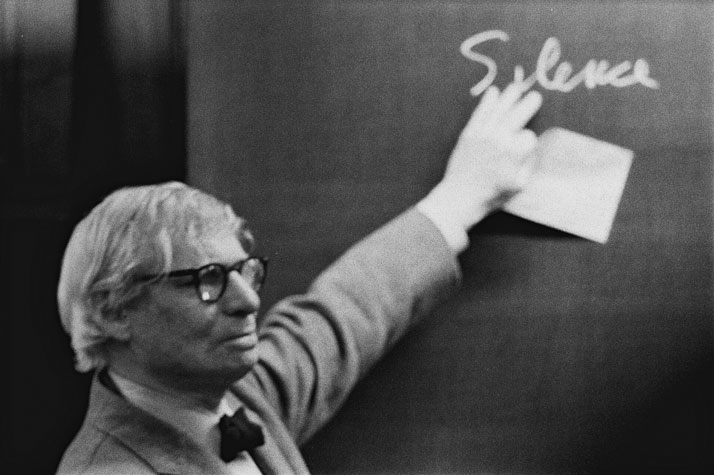

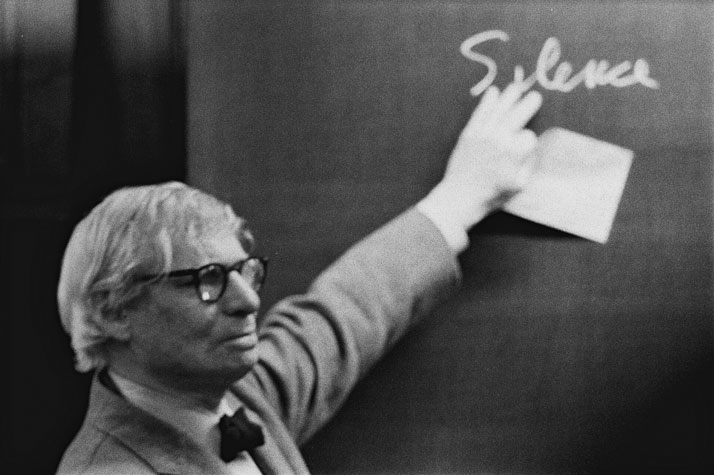

Louis I. Kahn during the lecture at the

ETH Zurich.

Louis I. Kahn during the lecture at the

ETH Zurich.

Photo by Peter Wenger © Archives de la construction moderne – Acm,

EPF Lausanne.

The cover of the book ''Louis I. Kahn-

Silence and Light'', © Park Books.

The cover of the book ''Louis I. Kahn-

Silence and Light'', © Park Books.

In 1974, Kahn died of a heart attack in a men's

restroom(厕所) in Pennsylvania Station in New York.

He went

unidentified(未经确认的)

for three days

because he had crossed out the home address on his passport. He had

just returned from a work trip to India.

Despite(尽管) his long

career(事业), he was deep in debt when he died. So in

answering the question ''

Can you get to know someone after

his death?'' the answer lies in the recent interest that

Kahn

has

piqued(赌气的). Asides from the exhibition at the Vitra Design

Museum,

Kahn and his

legacy(遗赠) live on through a recent publication

and soon to be released opera:

>>

His lecture ''

SILENCE AND

LIGHT'' which he gave on February 12,

1969 at the School of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute

of Technology in Zürich is also the title of a book recently

published by

PARK BOOKS, edited

by

Alessandro Vassella and forwarded by Indian

architect(建筑师) Balkrishna V.

Doshi. The lecture is represented

in

transcripts(成绩单)

in five different

languages - German, Italian, English, French, and Spanish - as well

as

a 60

minute audio recording of

Kahn

giving the lecture in English included

on a CD, gives us an

opportunity(时机) to discover the man’s spiritual

understanding of

architecture(建筑学), which goes far deeper than simply constructing

buildings.

>>

Entitled ''

ARCHITECT'', the opera

composed(构成) by Pulitzer Prize-winner

Lewis

Spratlan with

librettist(歌词作者)

and

electro(电镀物品) acoustic(原声乐器) composers

Jenny Kallick

and

John

Downey, is an

instrumental(乐器的) and

vocal(歌唱的) music

blend(混合) drawn from acoustic recordings

within Kahn's buildings.

Unveiling(使公诸于众) the relationship between sound and

space, and the connection between the past and

present,

Kahn’s work and his

assertion(断言) that '

TO HEAR A SOUND IS TO SEE A

SPACE'', are brought back to life. The opera

is expected to be released at the end of July 2013 by

Navona Records.

***

Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture is on show at the Vitra

Museum until August 2013. Its next stop will be the London Design

Museum in 2014.

ARCHITECT by

Navona

Records.

(Featuring(起重要作用)

a

watercolor(水彩画) artwork by

Michiko Theurer

on the cover)

ARCHITECT by

Navona

Records.

(Featuring(起重要作用)

a

watercolor(水彩画) artwork by

Michiko Theurer

on the cover)

Louis Kahn at the

auditorium(礼堂) of the Kimbell Art Museum,

1972.

Louis Kahn at the

auditorium(礼堂) of the Kimbell Art Museum,

1972.

© Kimbell Art Museum, photo: Bob Wharton.

Colonnade(柱廊) on the north side, Kimbell

Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Louis Kahn, 1966–1972.

Colonnade(柱廊) on the north side, Kimbell

Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Louis Kahn, 1966–1972.

© 2010 Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, photo: Robert

LaPrelle.

Library, Phillips Exeter Academy,

Exeter, New Hampshire, Louis Kahn, 1965–72.

Library, Phillips Exeter Academy,

Exeter, New Hampshire, Louis Kahn, 1965–72.

© Iwan Baan.

Ponte Vecchio, Florence, Italy, Louis

Kahn, c. 1930.

Ponte Vecchio, Florence, Italy, Louis

Kahn, c. 1930.

© Private Collection, photo: Paul Takeuchi

2012.

Steven and Toby Korman House, Fort

Washington, Pennsylvania, Louis Kahn, 1971–73.

Steven and Toby Korman House, Fort

Washington, Pennsylvania, Louis Kahn, 1971–73.

© Barry Halkin.

Living-room of the Norman and Doris

Fisher House, Hatboro, Pennsylvania, Louis Kahn, 1960–67.

Living-room of the Norman and Doris

Fisher House, Hatboro, Pennsylvania, Louis Kahn, 1960–67.

© Grant Mudford.

Jewish Community Center, Ewing Township

(near Trenton), New Jersey, Louis Kahn, 1954–59. Exterior view of

the Bath House with a wall drawing at the entrance designed by

Kahn.

Jewish Community Center, Ewing Township

(near Trenton), New Jersey, Louis Kahn, 1954–59. Exterior view of

the Bath House with a wall drawing at the entrance designed by

Kahn.

© Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, photo: John

Ebstel.

Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research

and Biology Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Lousi Kahn,

1957–65.

Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research

and Biology Building, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Lousi Kahn,

1957–65.

© The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, photo:

Malcolm Smith.