We tend to think of the decades immediately following World War II

as a time of exuberance and growth, with soldiers returning home by

the millions, going off to college on the G.I. Bill and lining up

at the marriage bureaus.

But when it came to their houses, it was a time of common sense and

a belief that less truly could be more. During the Depression and

the war, Americans had learned to live with less, and that

restraint, in combination with the postwar confidence in the

future, made small, efficient housing positively stylish.

As we find ourselves in an era of diminishing resources, could

“less” become “more” again? If so, the mid-20th-century building

boom might provide some inspiration.

William

Zbaren Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed these towers

on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive in the 1940s. They were recently

renovated.

William

Zbaren Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed these towers

on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive in the 1940s. They were recently

renovated.

Economic austerity was only one of the catalysts for the trend

toward efficient living. The phrase “less is more” was actually

first popularized by a German, the architect Ludwig Mies van der

Rohe, who like other people associated with the Bauhaus emigrated

to the United States before World War II and took up posts at

American architecture schools. These designers, including Walter

Gropius and Marcel Breuer, came to exert enormous influence on the

course of American architecture, but none more so than Mies.

Mies’s signature phrase means that less decoration, properly

deployed, has more impact than a lot. Elegance, he believed, did

not derive from abundance. Like other modern architects, he

employed metal, glass and laminated wood — materials that we take

for granted today but that in the 1940s symbolized the future.

Mies’s sophisticated presentation masked the fact that the spaces

he designed were small and efficient, rather than big and often

empty.

The apartments in the elegant towers Mies built on Chicago’s Lake

Shore Drive, for example, were smaller — two-bedroom units under

1,000 square feet — than those in their older neighbors along the

city’s Gold Coast. But they were popular because of their airy

glass walls, the views they afforded and the elegance of the

buildings’ details and proportions, the architectural equivalent of

the abstract art so popular at the time.

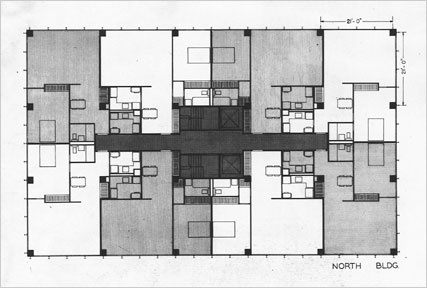

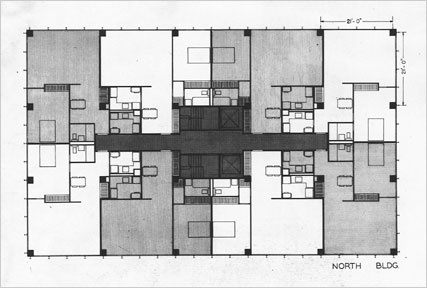

Museum

of Modern Art. Mies van der Rohe Archive, gift of the

architect A Ludwig Mies van der Rohe floor plan for a

860/880 Lake Shore Drive apartment building in Chicago,

1951.

Museum

of Modern Art. Mies van der Rohe Archive, gift of the

architect A Ludwig Mies van der Rohe floor plan for a

860/880 Lake Shore Drive apartment building in Chicago,

1951.

Tom Wolfe’s “From Bauhaus to Our House” aside, the trend toward

“less” was not entirely foreign. In the 1930s Frank Lloyd Wright

started building

more modest and efficient houses — usually around 1,200

square feet — than the sprawling two-story ones he had designed in

the 1890s and the early 20th century.

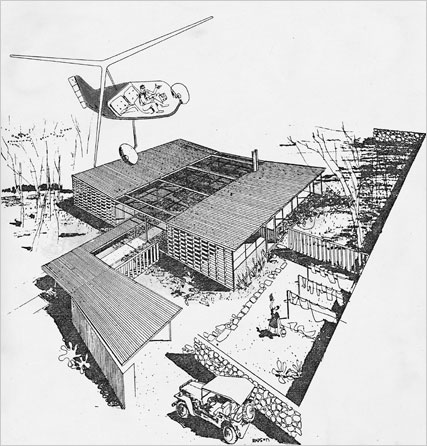

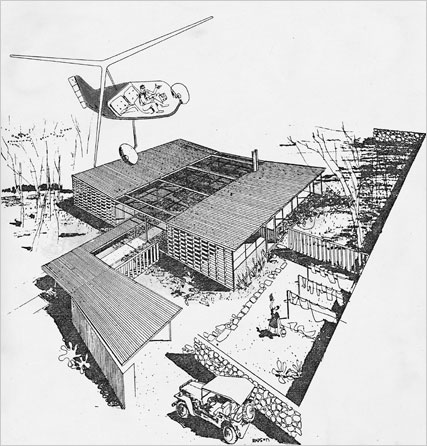

Rapson

Architects Drawing of a “Case Study House” by Ralph

Rapson.

Rapson

Architects Drawing of a “Case Study House” by Ralph

Rapson.

Even the consciously trend-setting Museum of Modern Art promoted

restraint in the early postwar years. In 1945, it held an

exhibition entitled “Tomorrow’s Small House: Models and Plans,” and

the pioneering model houses that Marcel Breuer and Gregory Ain

erected in the museum garden were small and sparsely

detailed.

The “Case Study Houses” commissioned from talented modern

architects by California Arts & Architecture magazine between

1945 and 1962 were yet another homegrown influence on the “less is

more” trend. Aesthetic effect came from the landscape, new

materials and forthright detailing. In his Case Study House, Ralph

Rapson may have mispredicted just how the mechanical revolution

would impact everyday life — few American families acquired

helicopters, though most eventually got clothes dryers — but his

belief that self-sufficiency was both desirable and inevitable was

widely shared.

Rapson

Architects Model of the interior of a Ralph Rapson

“Case Study Home.”

Rapson

Architects Model of the interior of a Ralph Rapson

“Case Study Home.”

“Less is more” wasn’t for everyone; modernism was popular mainly

with the so-called “Progressives,” the professionals and

intellectuals who commissioned modern houses. But these

trend-setters were not alone in assuming there would be fewer

servants in the future and that modern conveniences would make

housework easier to do, especially in smaller quarters.

Levittown

Public Library, via Associated Press New residents

moved into their home in Levittown, N.Y. in 1947.

Levittown

Public Library, via Associated Press New residents

moved into their home in Levittown, N.Y. in 1947.

The popularity of simpler living made it possible for one American

developer, William Levitt, to realize the prewar dream of the

European modern architects to use industrialization for housing.

During the war, Levitt had become an expert in mass-producing homes

for shipyard workers in Virginia. When it ended, Levitt and his

sons created a prototype 750-square-foot, one-floor house—with a

living room, kitchen/dining area, two small bedrooms, a bathroom

and an unfinished “expansion attic”—to fit on a 60 x 100 foot lot.

Set on concrete slabs like those at the shipyards, the new houses

were built quickly and cheaply on a sort of assembly line, with

pre-cut lumber and nails shipped from the Levitts’ factories in

California.

Eventually, the Levitts built 140,000 houses, clustered in

Levittowns on Long Island and near Philadelphia for some of the 16

million returning veterans. In the 1950s, the houses grew slightly,

to 800 square feet, and came equipped with carports and built-in

12.5-inch Admiral TVs. Clearly no one considered multiple

televisions, or that they would be frequently replaced.

Related

More on design and architecture.

The Levittown houses were concentrated on the East Coast, but they

influenced suburban development throughout the United States,

though elsewhere houses were built manually, as they would be after

the postwar building boom. The standard two-bedroom house with an

expandable attic became the norm for more than a decade, even as

family size mushrooomed.

But like much of American society, the middle-class home began to

grow over time. The average size of an American house in 1950 was

983 square feet. Slowly, though, both more square footage and more

amenities became part of the American dream, so that by 2004 the

average home topped 2,300 square feet.

What does all that space bring? Small, out-of-the-way bedrooms like

those in the Levittown houses’ “expandable attics” can be used when

children are at home or guests arrive, and the open plan of their

main living spaces has become the kitchen/family room that is the

center of the American home today. But many of the “must-have”

elements in 2010, like formal living and dining rooms, are

redundant. In an era of economic austerity and a seemingly

permanent energy crisis, can “less is more” become popular

again?

Sadly, many of the small, architect-designed houses of the postwar

period have been demolished to make way for McMansions. But those

that remain, and those we know about from blueprints and

photographs, have much to teach us — about the efficient use of

space for storage, integrated indoor and outdoor space and the way

careful design can facilitate natural ventilation. When you think

about how many rooms you actually use, it seems obvious that

various ideas from that optimistic era could make the next decade a

happier, saner one than the overstuffed times we’ve just lived

through.

(Note: An earlier version of this article misattributed the

origin of the phrase “less is more” to the architect Ludwig Mies

van der Rohe. He did not coin the phrase, but adopted and

popularized it as an aesthetic maxim.)

Jayne Merkel is an architectural historian and critic. She is

the author, most recently, of “Eero Saarinen.” She is a

contributing editor of Architectural Design/AD magazine and

Architectural Record.

Jayne Merkel is an architectural historian and critic. She is

the author, most recently, of “Eero Saarinen.” She is a

contributing editor of Architectural Design/AD magazine and

Architectural Record.

Living

Rooms explores the past, present and future of domestic

life.

Living

Rooms explores the past, present and future of domestic

life. Living

Rooms explores the past, present and future of domestic

life.

Living

Rooms explores the past, present and future of domestic

life. William

Zbaren Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed these towers

on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive in the 1940s. They were recently

renovated.

William

Zbaren Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed these towers

on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive in the 1940s. They were recently

renovated. Museum

of Modern Art. Mies van der Rohe Archive, gift of the

architect A Ludwig Mies van der Rohe floor plan for a

860/880 Lake Shore Drive apartment building in Chicago,

1951.

Museum

of Modern Art. Mies van der Rohe Archive, gift of the

architect A Ludwig Mies van der Rohe floor plan for a

860/880 Lake Shore Drive apartment building in Chicago,

1951. Rapson

Architects Drawing of a “Case Study House” by Ralph

Rapson.

Rapson

Architects Drawing of a “Case Study House” by Ralph

Rapson. Rapson

Architects Model of the interior of a Ralph Rapson

“Case Study Home.”

Rapson

Architects Model of the interior of a Ralph Rapson

“Case Study Home.” Levittown

Public Library, via Associated Press New residents

moved into their home in Levittown, N.Y. in 1947.

Levittown

Public Library, via Associated Press New residents

moved into their home in Levittown, N.Y. in 1947.